|

| Margaret and Julius Spadoni |

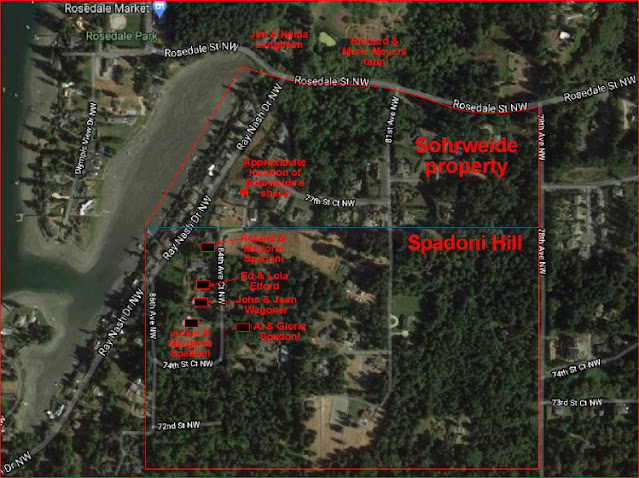

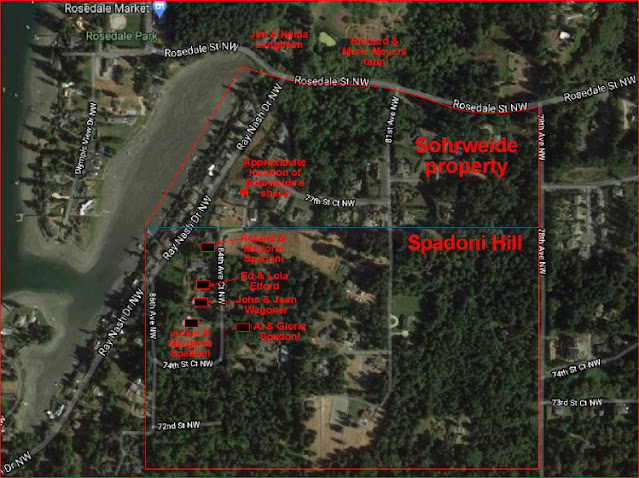

Chapter 2My parents, Julius and Margaret Spadoni, bought 100 acres in

1946 from Blanche Grant, whose father Joseph Oakes had homesteaded the land in

the latter half of the 1800s. The west side of this 100-acre Rosedale parcel,

overlooking Henderson Bay and the Olympic Mountains, later came to be known by locals

as Spadoni Hill, so-named not just because of my parents’ ownership and

residence there, but also because they sold parcels to four of my dad’s relatives

and to my mom’s parents, all of whom built there in the 1950s. The Oakes

homestead also included another large parcel to the north, about 50 acres,

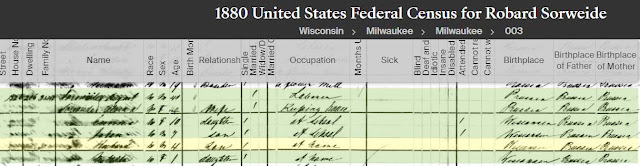

which records show was purchased by “R.A. Sohrwide” July 25, 1929, from

Christina and Donald McPhee. The land had changed hands four times since Oakes

died in 1890, but none of the subsequent owners had lived on it. The

fascinating account of homesteader Joseph Oakes and his heirs is told in a well researched story by Greg Spadoni that can be accessed by clicking here.

Reading about Oakes and the early history of the property

prompted me to do some research about the equally interesting story of Raynard

(sometimes spelled Reynard or Reinhard) Sohrweide. I was introduced to

Sohrweide by John Wagoner, my grandfather on Mom’s side, and one of Sohrweide’s

few friends in his days in Rosedale.

John and Jeannette Wagoner were the first to build on Spadoni

Hill, living in a small wooden cabin they built in the late 1940s, on the

parcel now occupied by Dennis and Sherrie Peters. While living in the cabin,

John and Jean dug a well and built a concrete block house that they lived in

while they built a still larger orange brick home. The cabin is long gone, but

the other two buildings still stand. Dennis and Sherrie use the concrete block

building as a garage, and they live in the brick home, although they have since

added a second story.

Dad, Mom and my sister Linda and brother Roger then lived in

the Wagoner’s block house while dad built another house next door, now occupied

by Paul and Becky Floyd. I was born in 1953, the year our family moved into the

partially completed new house. Linda and Roger remember sleeping out in the

original one-room cabin on occasion, but it was torn down in the early 1950s,

and it’s only a foggy memory to me.

Shortly after the Wagoners and my parents built on the hill,

other relatives joined them: Ed and Lola (Dad’s sister) Elford, Al and Gloria

Spadoni, and Roland and Marjorie Spadoni—whose house at the end of the road was

closest to Sohrweide’s. In the late 1960s, Roy and Marie Anderson—at one time

the only non-relatives on the hill—built a house between the Elfords and Roland

and Marjorie in the 1960s. After Sohrweide’s death, two other relatives built

houses pretty much where the goat man’s house had been.

Sohrweide and Grampy, as we kids called grandfather Wagoner,

got along quite well and visited regularly. I remember going with Grampy at

least once to visit Sohrweide in his one-room cabin, but being very young, the

significance of the meeting was lost on me. I remember almost nothing, except

an image of a patchwork shingle roof, Sohrweide’s old woodstove and the smell

of wood smoke.

|

While the aerial photo is current and is taken from Google Maps, the boundaries and homes

shown were as they existed in the 1950s, when Ray Nash Drive NW was located right

along the waterfront. Both properties were otherwise unoccupied by homes. |

My cousin Greg, son of Al and Gloria also remembers Grampy

taking him to visit Sohrweide. The visit made a lasting impression.

“I couldn’t have been more than five,” he said. “Mr. Wagoner apparently thought

it would do us little kids good to see him check up on an invalid. Whether

it was to introduce us to the cycle of life or to see how important it was

to check on the welfare of neighbors, I don’t know. Maybe both.

Maybe something more. In any case, I never forgot it.”

For some reason, people on the hill always pronounced his name

shore-widey instead of sore-widey. Maize said she actually thought his name was

pronounced shore-whitey. However, other people in Rosedale who knew him pronounced

his name correctly.

Sohrweide did have other friends, including Peter Land and

Borghild Jensen Anderson. Kevin Meyer, brother of Dick, said that his

grandmother Anna Meyer would sometimes bring meals to Sohrweide. Borghild’s son

Joel said Sohrweide would occasionally drop by his house to visit with his mom.

Nonetheless, the goat man became progressively reclusive as he aged. Land died

in 1957 and Wagoner in 1962, so when Sohrweide died in 1969, his small circle

of friends had dwindled. While I’m sure that Land, Wagoner and Anderson

probably knew quite a bit about Sohrweide’s background—and probably my parents

did as well—much of his life was a mystery to those of us who grew up around

him from the 1950s onward. We didn’t know when he moved there. To us, he had

always been there.

“I didn’t know that the property had been homesteaded before,”

Linda said. “I just thought Sohrweide had lived there forever. You know how it

with little kids. It is how it is, and that’s how it must have been.”

Carol Spadoni Parker, daughter of Roland and Marjorie and

Linda’s childhood best friend, said, “He may have homesteaded the property. I’m

pretty sure he once had a regular job. I think my dad knew what he had done for

a living, but I don’t know.”

Joan Anderson Adler, one of Borghild’s daughters, said she

thought Sohrweide probably homesteaded the land. She also had some interesting

but ultimately inaccurate theories about his earlier years. “I believe his wife

came with him, but she died very early on. Apparently, he became a recluse

after his wife and child died. As I recall, it was probably in childbirth, and

from then on, he just closed up on himself and the world.”

One of Joan’s childhood friends, Rosemary Land Ross, recalls

the common bond that Sohrweide and her father shared: “My father Peter Land and

Mr. Sohrweide were very good friends and would get together because they shared

a common heritage; they were both from Germany. As a child I can remember going

with friends, and we would see how close we could get without him finding out

that we were trying to sneak up on the little encampment that he had. He would

never lift a hand to hurt anybody. He was perfectly harmless. I quite often had

to do my best to avoid his goats because I walked past them every morning on my

way to school.”

“He was definitely a part of our childhood, in a strange way,”

Joan said. “There was a fascination. I’d walk down to Rosemary’s house, and

we’d look up the hill and wonder if we’d see him. We never saw him while

walking by, but we were always aware that he lived up there.

“He was just such a character, kind of exotic to those of us

growing up in a small place like Rosedale. It was just part of the color of the

community, one of the fun and odd parts of childhood. It was fascinating because

we didn’t really know him. We’d just see him once in a blue moon. He certainly

wasn’t a mixer.”

Those of us living on Spadoni Hill during the earlier years

probably saw him most often, mainly because of his friendship with Grampy.

“In the summers, his well would go dry, and he’d come with a

couple of buckets to get water,” Linda said. “He spent a lot of time making

trails through the woods and lining them with rocks along the side. I don’t

remember him ever having a house, just a little shack under a big maple tree.

“Carol and I would make cookies sometimes, and we’d put them

at the edge of the trail with a note that they were for him. And then he’d

leave the empty pans with a note that said thank you. But we never knew if he

actually ate them or not.”

Borghild Anderson would also leave packages for Sohrweide in

his mailbox, said Joan. “Mother was somebody who loved people, and she would

leave him things she had baked. And then he would write her a beautiful,

educated letter back, using strange paper that was not stationery. It might

have been the back of a light-colored paperback. His handwriting and his

language was beautiful. It was always interesting to us.”

While Sohrweide enjoyed Grampy’s company and trusted him, he

initially did not have much love for the other occupants of Spadoni Hill. He

seemed to feel that we were intruding in his world, perhaps because our houses

were close to his.

“He once said that John Wagoner was a good man, but it’s too

bad he’s associated with those Spadoni commune-ists,” Roger said, explaining

that because all the families on the hill were related and worked closely

together, it was tantamount to living communally.

“One time when Dad and Roy were selling some logs,” Linda

said, “they went to Mr. Sohrweide and asked if he wanted to sell some trees to

get some money. He said no way. He thought it was a plot to get his land; the

Spadonis wanted to steal his trees, and he said absolutely not.”

Sohrweide instead hired Bill H. Sehmel, his son Charlie and

Lyle Severtson to do the logging in the late 1940s. Shortly after that,

Sohrweide obtained a truck, which lasted only a few years. The truck was either

made in the 1930s or 1940s, depending on who is doing the remembering, and it

was in running condition up until the early 1950s.

“When I first moved up here,” Linda said, “he had a rickety

old truck. He’d just let his goat wander, and they’d go all over the area. And

somebody would get him a message that his goats were in their garden, and that

if you don’t come to get them we’ll shoot them. Sometimes he’d go get them in

that rickety old truck. One time I saw him coming back with a dead goat tied to

the front. A person had shot it.”

The truck is another part of the intrigue of Sohrweide’s

legacy, and it reveals another aspect of his evolving personality—borderline or

outright paranoia.

“He felt people were out to get him,” Linda said. “Everything

bad that happened was somebody’s bad plan, that they were out to get him. Every

time he got sick, he thought that it was because somebody put poison in his

well to get his land or steal his truck.” The truck is a good example of his

paranoia.

“When his truck quit

running, some teenage boy from around here told him he could fix his truck for

him,” Linda said. “Then the old goat man figured that now somebody could steal

his truck, so he put sand in the gas tank and chained it to a tree. That was

what I heard. And if you went and looked, it was chained to a tree. I never

looked in the gas tank.”

Jim Langhelm provided more information on the truck incident:

“Someone talked Sohrweide into letting them do some logging on the property,

and as partial payment they gave Sohrweide an old truck, which soon broke down.

Gary Michaels offered to fix it, but then Sohrweide changed his mind.”

How true is the story about the truck? Charlie Sehmel does not

remember anything about giving Sohrweide a truck. It is possible that Sohrweide

bought the truck with proceeds from the timber instead. It also seems likely

that the loggers put in a road leading through the Spadoni Hill property. The

road soon grew over and became only a trail once Sohrweide stopped driving the

truck.

“I don’t recall ever seeing him driving the truck on the

county roads,” Jim Langhelm said. “I had it in my mind that he didn’t know how

to drive it. I also don’t recall any of the few ‘logging roads’ that were put

on his property ever exiting out on to any of the county roads. I think his

only road access was off the end of your road on the hill at Roland’s house.”

Roger, however, does recall a road from Sohrweide’s land that

accessed Rosedale street, and it was likely that at least during the times the

loggers were active, there were two ways to enter the property: off Rosedale

Street and through Spadoni Hill onto what is now called 84th Avenue Court NW.

I was able to track down Gary Michaels to get his version:

“Mr. Sohrweide was a paranoid recluse and a bigtime hoarder. He had a lot of

junk around his house, and if you looked in the front door there was stuff

stacked to the ceiling with a narrow walkway through his living space. Carl

Jacobson and I tried to befriend him in our high school days (1956-57). We had

our own junk business collecting scrap metal, old cars and anything else of

value, selling what we could find to old Joe Sussman at his scrap business in

Tacoma. Since we were looking for scrap, the goat man was a logical fellow to

cultivate. We did convince him to let us try and get his late 40s Chevrolet

pickup running but were unsuccessful. As a last resort, we attempted to start

it by rolling it downhill. Failing to get it started was the last straw. By

then, the goat man was sure we were trying to steal his truck, so he chained it

to a tree. That was the end of our relationship with the goat man.”

What became of that Chevrolet truck is unknown. However, he

also had an older truck, which my brother Roger believes was a Model A or T

Ford. Roger remembers both trucks, and he and cousin Alan Spadoni (the late son of

Roland and Marjorie and brother of Carol) actually spent time playing on the

old Ford. Roger and Alan, it seems, were only young people on Spadoni Hill who

were not afraid to go on Sohrweide’s land.

“We asked him if we could play on it, and he said yes,” Roger

said. “At that time, I was probably 12 or 13, and it wasn’t in a condition to

be repaired. It was probably salvageable for parts.” Roger was born in 1947, so

this would have been around 1960, perhaps four years after Gary Michaels and

Carl Jacobson tried to get the newer truck running.

“He didn’t seem unfriendly to me,” Roger said of Sohrweide.

“Maybe a little suspicious the first time we knocked. He said that other kids

would sometimes knock on his door and then run away.”

In any event, to Roger and Alan’s disappointment, the old Ford

disappeared shortly after Sohrweide went to a nursing home in the early 1960s.

“Less than two weeks after he went to the nursing home, somebody came in with a

bulldozer and towed his truck out of there,” Roger said. “Alan and I kind of

had our eyes on it. We followed the tracks right out to Rosedale Street.”

Roger speculated that maybe one of the loggers who purchased

and harvested trees on the land had also coveted the relic. However, it seems

more likely that Sohrweide needed money to pay for his health needs, and either

he or a family member or friend arranged a sale. It’s probable that the

Chevrolet truck was hauled away at the same time.

Continue to chapter 3