Chapter 4, The Old Goat Man of Rosedale

Maize said she understood that “he was an inventor and had

notebooks full of the things he wanted to invent.”

Linda and Roger both felt he must have had an engineering

background because of the ideas and drawings he had showed our grandfather.

“He had approached Grandpa with two ideas,” Linda said. “He

spent a lot of time making big engineering sorts of plans. He wanted Grandpa to

get somebody to listen to him, because he had a way to get more power out of

Grand Coulee Dam, with engineering. He showed Grandpa the plans for it, and

Grandpa said they looked like real plans, but he wouldn’t have any idea who to

approach to tell them how to do that.”

However, Sohrweide’s engineering prowess did not impress

everyone. Greg tells this tale: “When we were kids, one of the stories about

Sohrweide was that he had a plan on how to increase the electrical power output

of the Grand Coulee dam, but that nobody at the dam would listen to him. Us

being kids, we thought maybe he had something on the ball. In the 1970s I asked

Julius about it. He kind of scoffed with a chuckle and said that Sohrweide’s

‘plan’ was to extend the length of the turbine blades in the

generators, giving the water flowing through the dam more leverage. For anyone

who doesn’t get why no one at the Bonneville Power Administration would listen

to Sohrweide, it would be akin to contacting NASA and telling them that the

next time they launch astronauts into space, they should point the rocket up.”

His other grand scheme—which he told to John Wagoner—was more

local—and definitely more fanciful.

“His original plan had been to buy all the property on both sides of the lagoon and put a dam at the end of it to hold the water in,” Linda said. “And then he would use the trees along the lagoon to build treehouses and make a honeymoon haven of treehouses. But he needed somebody to pitch in money to help him do that. Grandpa didn’t think that was possible, so he didn’t pitch in any money.”

|

| Linda, Roger and Paul Spadoni |

As our research shows, though, Sohrweide was neither an

engineer nor an inventor, and he seemingly had a fairly normal life for at

least his first 30 years. Then he became a bit of a drifter for the next 25

years, though he still lived in mainstream society, before he finally ended up

in Rosedale—where he became a little more estranged from society each year. He

spent his last seven years in a Tacoma nursing home.

Reinhard August William Sohrweide was born December 31, 1875,

to August Ferdinand Friedrich Sohrweide and Alwine “Alvina” Louise Friederike

Auguste Maass in 1868 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. His parents were both born in

Prussia, Germany, and immigrated to the United States in 1865 and 1867,

respectively. The name Sohrweide comes from two German words: Sohr,

meaning dry or withered, and weide, meadow or grassland. The census shows that other

Sohrweide families already lived in Milwaukee, no doubt relatives, who would

have helped August and Alvina get settled.

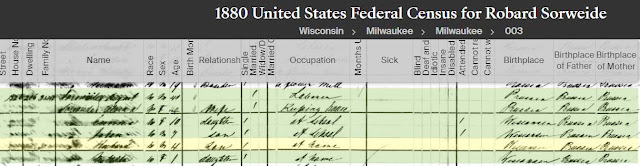

|

| This shows Reinhard as 4 years old in the Milwaukee federal census of 1880, though the person who placed it in the index interpreted his difficult-to-read name as Robard. |

Raynard Raynard went by the name Reinhard until his mid-twenties, when he decided to use a more American-sounding name. He often just used his initials, R.A. He had two sisters, Emma (1870) and Martha (1879). His brother Johann, three years older, legally changed his name to John in 1902. August, Johann and Reinhard are all listed at the same address in Milwaukee in 1893. August is listed as a laborer, Reinhard as a carpenter and Johann as upholster. In 1896, the directory is the same, except Reinhard is now an upholster like his brother. The next year, Reinhard and Johann moved to Denver, Colorado, and in the 1898 Denver directory, they are sharing a room and working as upholsterers for E.C. Hartshorn. The next two years, the brothers have separate addresses but are still working for Hartshorn, and on March 20, 1901, Raymond Sohrweide married Amy Blanche Pearman. In January of 1902, Blanche (she went by her middle name) gave birth to Dorothy Mary, and in 1904 to Leroy Ambrose.

|

| Sohrweide's wife Blanche is shown on the far left in this family taken late in her life with some of her brothers and sisters. |

Among other things, SM&U made custom mattresses for boats,

and it could have been this connection that led Raynard to future work in the

fishing industry during his years in Seattle. On his 1918 draft card, he is

working for the Puget Sound Bridge and Dredging Company, and in the 1919

Seattle directory, his occupation has changed to shipworker. Sometime in the

1920s, he purchased a used fishing vessel—probably a gillnetter, since the

records say it had a crew of one—and lived on it. This can be surmised because

on his boat registration papers for 1928 and 1931, his address is written as

“care (of) 5016 W. Marginal Way,” which was the home of Edward Wislocker, a

ship’s carpenter. This was also Sohrweide’s address in the 1927 Seattle

directory, which again listed him as an upholster. He also spent some time in

Tacoma and can be found in the 1924 Tacoma directory working as an upholsterer

for the Washington Parlor Furniture Company, Inc.

When he purchased the Rosedale property in 1929, he was still

living on his boat, and most likely, he piloted the boat to Rosedale and

continued to live in his boat until his cabin was habitable. It’s not clear

when he moved on shore. He is not listed in the 1930 Rosedale census. Dick

Meyer Sr., who was born in 1931 and grew up his family’s farm, recalls seeing

Sohrweide’s boat in the Rosedale lagoon.

It’s also not known whether Sohrweide built his shack or

instead refurbished whatever was left over from the days when Joseph Oakes

homesteaded the land. It is quite likely that any fruit trees on the land were

holdovers from Oakes, as Greg Spadoni’s research showed that Oakes planted 240

fruit trees from 1884 to his death in 1890.

“It looks to me like Sohrweide might have been living in the

original homesteader’s house, although it could’ve been the second house on the

land,” Greg said. “If the original house still existed, it had to have been

pretty dilapidated when Sohrweide bought it, because Dick Meyer told me that

Sohrweide lived on a broken-down fishing boat in the lagoon until it

rotted out from under him. You’d think he would’ve lived in the house if it was

in decent condition, but that’s probably something else we’ll never know.”

Sohrweide is listed in the 1940 census, which also has a

column that asks whether the person lived in the same place in 1935, and he was

there then as well. The census also states that he had attended school through

the 8th grade and his house was valued at $500.

Though he lived alone, his reclusive and suspicious nature probably did not manifest itself in his early years in Rosedale, as many of us who were children in the 1950s recall that our parents and grandparents were on friendly terms with him. Maize recalls that Raynard’s brother sometimes came to visit. And while many who knew him in his later years described him as paranoid, some of that can be attributed to the fact that people have told tales of sneaking around Sohrweide’s house when they were kids, hoping to see him without being detected. As the character Harold Finch in the 2015 movie Asylum said: “It’s not paranoia if they’re really out to get you.”

|

| Members of the Upholsters International Union |

Continue to chapter 5

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments welcome.